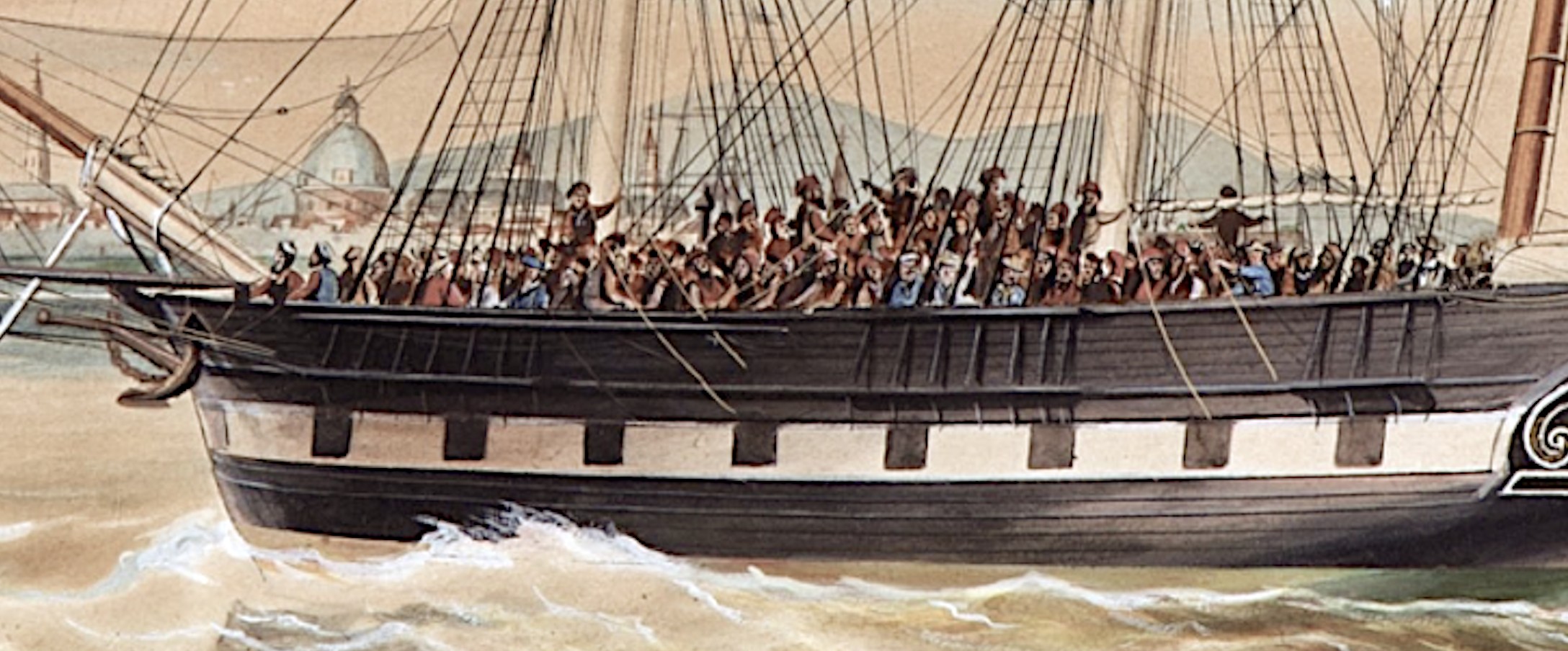

A crowd on deck

The watercolor pictured here painted by Jacob Spin in 1850 of two Dutch barques approaching Manila on March 31, 1849 comes up for sale at an Indonesian art auction at the Venduehuis in The Hague on November 18, 2020 ((‘Lot 1,’ Venduehuis, Indonesian Art Sale, 18 November 2020)). It has been around in the art market for some time, having been sold at Christies in 2011 ((‘Lot 52,’ Christies Amsterdam, 20 September 2011)). From a marine painting point of view the work is of modest quality and interest, although taken as a whole the hundreds of ship paintings made by Jacob Spin of Amsterdam, a sailor turned artist, are a wonderful encyclopedia of global trade and the maritime history of the Netherlands in the early 19th century. A recently established foundation seems to be patiently working on a complete catalogue of his work ((www.jacobspin.nl)).

What captured our interest however, is the presence on deck of an unusual Delacroixian crowd of people, which made us believe this painting was not only a proud owner’s or captain’s commission, but also the registration of a special event ((See Eugene Delacroix: Liberty Leading the People on Wikipedia, retrieved on 8 November 2020.)). But what event? Words on the back of the painting don’t say all, but do mention the barque Reijerwaard commanded by captain P. Wierikx arriving in Manila on the 31st of March 1849, but not why all these people crowded her deck. Fortunately both the painting itself, the digitalized Dutch newspaper archives of Depher and the efforts of amateur ship enthousiasts helped us out.

About the ships

Both ships in the painting are flying the city of Rotterdam’s green and white flag with a number identifying the captain. On the foreground there is “R 6” written in the flag, while the second ship flies “R 159,” which according to the authors of the website scheepsindex.nl corresponds with captain Geert Franse Rijken commanding in 1848-1850 the Gouverneur Generaal Rochussen owned by Joost van Vollenhoven of Rotterdam ((‘Kapitein Geert Franse Rijken,’ on scheepsindex.nl)). And “R 6” is said indeed to identify captain Petrus Wierikx (1816-1892) commanding Reijerwaard from 1848 to 1855 for owner Fop Smit of Kinderdijk, which is upriver from Rotterdam ((‘Kapitein Petrus Wierikx,’ on scheepsindex.nl)). The Reijerwaard was just new in 1848 and was built by the owners family. It had copper plating on its hull and was advertised by agents as having been specially designed and outfitted to carry some passengers ((‘Schepen in lading,’ in Nieuwe Rotterdamsche courant, 8 September 1848)). One can track the ship in newspapers from 1848 to 1855 on its way between Rotterdam, Britain – often Newport, Monmouth -, Singapore and the ports of Java in de Dutch East Indies, in which ports it usually picks up mostly coffee, sugar and tin, but is also boarded for passage home by, for example the influential and rich politician Van Hogendorp and his family ((‘Vertrokken van Banjoewangie,’ De Oostpost, 15 February 1854, on delpher.nl)). The ship advertises in newspapers its good reputation which may result from luxury and speed and its owner Fop Smit having built the steam tug Kinderdijk which would bring sailing ships into port even if the wind failed ((‘Het begin van de sleepvaart,’ on www.zeesleepvaart.com)) ((‘Hellevoetsluis den 22 dezer,’ in Rotterdamsche courant, 24 May 1853)). The second ship in the back of the painting, the Gouverneur Generaal Rochussen, was also new in 1848 and outfitted to accommodate luxuriously passengers and even had a competent ship’s doctor on board; so advertise its agents in July 1848 ((‘Schepen in lading,’ Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, 24 July 1848)).

Charted by the Dutch East Indies government to transport 300 Spanish deportees and 50 soldiers to Manila in the Philippines

An essential piece of information explaining the crowd on the ship’s deck does exist and comes from the trade news pages of the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche courant of 20 April 1849. The paper informs the Reijerwaard and Rochussen were chartered together by the Dutch East Indies government to transport over 300 Spanish deportees and 50 soldiers to Manila. They had arrived in Batavia on board the Spanish ship Colón, which had been heavily damaged in a storm and apparently wasn’t able to continue its journey ((‘Handelsberigten. Batavia, 24 Februarij,’ in Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, 20 April 1849.)). The Colón was probably not a steamship of the same name that went to sea in 1848, but an older sailing vessel. A ship named the Colón passed Sunda strait in 1841 on its way from Cádiz to Manila captained by a Don Lucas Zasso. The local newspapers reported such passages between the islands of Sumatra and Java ((‘Scheepsberigten. Straat Sunda. Doorgezeild.’ In Javasche Courant, 5 May 1841.)). Reijerwaard and her companion didn’t stay long in Manila. Having arrived on March 31 delivering their involuntary passengers, they sailed again on April 4 ((‘Scheepstijdingen,’ Algemeen Handelsblad, 28 June 1849.)). Whether the deportees, while stranded by that storm in Batavia, requested their freedom of the government of the Dutch East Indies and why and how that government decided to charter ships to send them on to Manila didn’t become clear in any of the newspapers. It appears there is not a single other mention of the deportees or the Colón and neither do the National Archives in The Hague easily produce a dossier about the case.

Deported from Spain to the Philippines

So who gets deported from Spain? One can follow broadly what happens in Spain in 1848 in Dutch newspapers of the period. In March there is news from Bilboa that Carlists, conservative supporters of a competing branch of the Spanish royal family, have been inspired by events in Paris where king Louis-Philippe abdicated in February ((‘Frankrijk,’ Bredasche courant, 17 March 1848)). A month later news arrives through Paris from Catalonia that Carlists there are trying to make revolution, followed shortly by news of Carlists and ‘progressists’ having joined forces ((‘Frankrijk,’ Utrechtsche provinciale en stads-courant, 26 April 1848)). Young people are running from their parents and taking arms belonging to soldiers lodged with them. Soldiers too are joining the uprising ((‘Spanje,’ Utrechtsche provinciale en stads-courant, 1 May 1848.)). In the months of June and July reports appear of limited struggles and rumors of invasions by Carlists and progressive forces assembling around the border with France. But by the end of July the news is that the Carlists are failing to inspire the people to rise and shortly after in August are being defeated in the cities, but still fighting from the mountains ((‘Parijs,’ Opregte Haarlemsche Courant, 24 July 1848, ‘Parijs,’ ibid, 5 August 1848.)). Of most interest however for us is a report from Madrid of September 2nd that in Catalonia Carlists are still being hunted down and that a number of prisoners, mostly caught in Catalonia, were transported to the Philippines ((‘Fransche Post. Madrid,’ Algemeen Handelsblad, 11 September 1848.)).

Departure of the Colón from Cádiz to Manila

It is surprising what one can find in Dutch newspapers of the time. The ‘Spanish mail’ section of a Rotterdam paper actually reports from Madrid about the deportees leaving Spain. ‘On the 22nd of this month [September 1848] 326 prisoners of the state have left from Cadiz for the Philippines on board the government’s frigate Colón ((‘Spaansche Post, Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant, 5 October 1848)).

Left wing revolutionaries and perhaps some Carlists

It would appear from the painting that some of the men on deck of the Reijerwaard are sporting a typical Basque style beret popular with the militant Carlists of the 1848 uprising. Indeed some of them were deported to Manila as a Dutch paper suggested, but there is an elaborate article written by a Juan Luis Bachero Bachero in the Spanish scientific periodical History Social which deals with deportees from 1848 and suggests otherwise. Bachero Bachero studied the Spanish government’s policies of the time and states that in a choice between Cuba or the Philippines only a few Carlists were sent to the Philippines, but that progressive revolutionaries with outspoken ideas, who the government feared might provoke uprisings among the creole population in the slave economy of Cuba, were singled out for transport to Manila. In the Asian colony they were at a greater distance from Spain and at the same time Manila might benefit economically from a middle class of artisans. The deportees to Manila, in total three transports of which the Colón was the largest, numbered around 740 and increased the Spanish population of the city by 50% ((Juan Luis Bachero Bachero: ‘La deportación en las revueltas Españolas de 1848,’ in Historia Social No. 86 (2016), pp. 109-131.)).

Returning home, but some executions too

The deportees didn’t have to stay long in Manila, Bachero Bachero informs us. A change in government in 1849 and the making of new laws allowed them to return to Spain as early as 1850, notwithstanding some difficulties getting the passage back home paid. Most of them seem to have returned, but not all. A Dutch local newspaper from the city of Arnhem reports in 1852 news from the Philippine Islands that “in Manilla 16 people were executed by firing squad after a conspiracy was discovered among the political deportees in that Spanish colony.” All did not end well for some of the deportees ((‘Engeland,’ Arnhemsche Courant, 28 April 1852)). Seeing the crowd on the deck of Reijerwaard arriving in Manila, we can just hope and deduct from the painting that captain Wierikx looked after them well during the final part of their voyage. In Manila they were put to work as carpenters, blacksmiths, bookkeepers, whatever their jobs home were, is not known. One of them was posted as a musician with the regiment in Luzon.